I was a young teenager on my summer vacation after my first year out of high school, when I was appointed by my father to accompany my invalid mother, who had suffered successive accidents that had rendered her virtually immobile and almost always in pain, to Chennai. There, Krishnamacharya, whom my father knew through a common friend, was going to use yoga to help her heal. For a young teen to be asked to spend her annual vacation in a city with no friends, and with nothing to do but to escort an infirm parent to some old healer every day, was not the most attractive deal. But my authoritarian father was not one to be questioned, and I resigned myself to my fate.

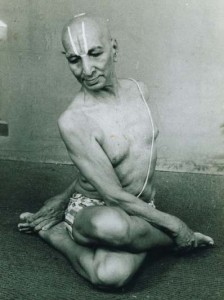

Every day, once in the morning and again in the early evening, my mother and I would take a taxi from our hotel to Krishnamacharya’s home for an hour’s instruction. He always appeared remote, wrapped in some self-sufficient world that did not require communication with visitors beyond classroom instruction. His was not a severe face; indeed it was a handsome sharp-featured one, with large luminous eyes and an enigmatic smile that lit up his features, although the reason for its existence did not seem to be to enhance social interaction. I don’t remember him ever make small talk, or even show the slightest interest in us beyond addressing my mother’s ailments. But he gave us his undivided and intense attention while teaching, and taught my mother with great gentleness.

Within a couple of days of starting her instruction, he seemed to notice my presence, and commanded me to take my place on another mat. I complied wordlessly; his voice did not give me a choice. For the next two months, every morning and evening, he taught me yoga with the same attentiveness that he showed my mother, even though teaching me was not part of the original understanding with him. He also taught me how to assist my mother in performing her asanas. He demanded the slowest of breathing and movement, and his hawk eyes never left me for a minute, making sure that every movement was executed absolutely correctly. I learnt to be terrified of him, as he was as ferociously strict with me as he was gentle with my mother. But I could also sense his restrained pleasure in seeing me respond easily to the instruction, young as I was and unhampered by ailments; and the perfection that he expected from every movement, and his unrelenting supervision, motivated me to try harder to come up to his expectations. By the end of our time with him, he had even taught me the Sirasasana (head stand).

At the end of the two months, our relationship with Krishnamacharya terminated as abruptly as it had begun. My mother had improved vastly. And I had discovered that I had a naturally supple body. We went back to our lives in Bombay and in due course, I stopped doing my yoga practice and forgot all about the old man who looked, lived and behaved like an ascetic, and who had introduced me to what was potentially a whole new world, a significance that I did not grasp at the time. My father – the family’s yoga enthusiast – continued to do his asanas (for which, mercifully, he attended a yoga institute closeby); but he would do what looked to me ghastly tricks – called kriyas – at home, like swallowing yards of cotton tape and pulling them out of his mouth. I sometimes watched from afar with morbid fascination. I did not want to be part of that obsession. It was also comforting to go back to being the couch potato that I was naturally inclined towards.

In modernizing metropolitan India of the time, yoga had not yet come of age in the popular consciousness, and it was generally seen as a traditional, ‘old people’s’ thing. For me, Krishnamacharya…my father…exemplified this. Sadly, as with most other things in India, it was the discovery of yoga by the West and its triumphant return to India from the global stage, borne aloft on the shoulders of B.K.S. Iyengar, that prompted Iyengar’s countrymen to pay attention to this ‘new’ form of ‘exercise’ and, indeed, way of life.

When I awakened to the benefits of regular exercise, my first instinct was – like my peers – to take to popular fitness regimens…aerobics, gym, jogging, karate… It was some time – and quite a few injuries later, born of over-enthusiasm and lax supervision – before my early influences caught up with me. I enrolled myself in my father’s yoga institute on Bombay’s Marine Drive. I had declared myself a beginner on the enrolment form. But the ease with which I was able to learn astonished even the teachers. I had underestimated the strength of the foundations that Krishnamacharya had laid. I particularly found his teaching of how to synchronise my breathing with my asanas, the stress on the sequencing of asanas, and the importance of being conscious of the correct structural alignment in every asana, coming back to me.

On professional trips abroad, I would meet people who raved about a man called B.K.S. Iyengar, and sometimes these trips coincided with Iyengar’s visits to these cities, and I would hear about hundreds of people attending a Master class by the visiting yogi. My curiosity about Iyengar was aroused, but I was still unaware that I too was part of this yoga web… albeit as an insignificant and unworthy strand. It was a chance visit to the Iyengar Institute in Pune (near Mumbai) which brought the memories of the old teacher rushing back.

I was in Pune with my family on holiday, and we happened to drive past a signboard on a gate announcing the B.K.S. Iyengar School of Yoga. On impulse, I hopped off telling my family that I would meet them back at the hotel. It was an intriguing looking campus, with complex yoga postures sculpted along the walls of the compound. I had never been in quite such a place. It looked a bit weird. I saw some lights on the first level, and my excitement mounted as I took the curving flight of stairs going up. I couldn’t believe that I had actually found the ‘source’ of the global phenomenon that was Iyengar! All those people in all those distant foreign countries waiting for him to turn up for a Master class… And here he was, in my own home, so to say…

At the top of the stairs I stopped short in total astonishment. On the wall to my left was a larger than life black and white portrait of Krishnamacharya, hands folded in namaskar, his luminous face and enigmatic smile exactly as I remembered it. I hesitated for a moment, staring at it …after all these years… what was the old man doing here? I raced across the hall to the lone person sitting behind one of the many empty counters.

“Excuse me”. He looked up with the blank clerical face that you see behind every counter in every office.

“The office is closed. Come back later”. And he went back to whatever he was doing.

“I need to know…Who is the man in that photograph?”

No reply.

“Who is he? And what is his connection with this place?”

He looked momentarily startled by the urgency in my voice (and probably as much by my question). But his clerical instinct bounced back. “I told you, no? Office is closed. Come back in the evening”.

I stood my ground and repeated my question twice more before he could bring himself to answer what he clearly thought was a lunatic woman.

“Why do you want to know?”

“Because I know him.”

He looked at me unbelievingly.

“Please tell me… why is he here? “ I was almost pleading for a reply.

“He is our guru’s guru”, was all he said.

I felt faint as I turned to leave. Here I was, full of admiration for B.K.S. Iyengar. And of course, for all the right reasons. But, we had actually shared the same guru! How much more unworthy could I have gotten? That, in all those intervening years I had not recognized the value of the instruction that I had received, or the person who had taught me, dismissing him as a crochety old man who had been a friend of my father’s?

Related:

The Story Of Yoga

A Guru’s Burden

Krishnamacharya Timeline

Credits: This story has been extracted from the post we ran into here, the full post also contains a biographic sketch of T. Krishnamacharya and is worth reading. We love this post as it provides us a glimpse of the healing powers that T Krishnamacharya bought to bear through yoga. It also provides us a glimpse of the unappreciated and unheralded life that T Krishnamacharya patiently lived in a India that was all too willing to give up its roots in the rush to embrace all that was modern.