A wonderful story unfolded when a cultured and refined western woman met some of the greatest yogis of recent times. The story starts in Florence, Italy in 1908 when Vanda Scaravelli was born. She was born into an artistic, musical and intellectual family. Her father was involved in creating the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino as well the Orchestra Stabile. Her mother was amongst the first women graduates from an Italian university. Many world-class musicians were frequent visitors at the family villa. Her father was also a successful businessman and the family was well off. Vanda herself trained as a concert pianist and was an accomplished musician.

Her father was a friend of the eminent Indian Philosopher J. Krishnamurti and in 1929 when Vanda was a young woman she met Krishnamurti for the first time. She also happened to attend the meeting when Krishnamurti announced that “Truth is a pathless land, and you cannot approach it through any track, religion, or any sect.” After his speech Krishnamurti dissolved the Order of the Star that the Theosophists had founded in his honor. This had a profound impact on Vanda and she would maintain a lifelong friendship with Krishnamurti. Once a year Krishnamurti visited the family and stayed in the villa outside Florence. Nobody expected him to be a guru and he could think and write in peace.

Vanda Scaravelli was married to a professor of philosophy, Luigi Scaravelli, with whom she had two children. She led a busy active social and cultural life. But in May of 1957 Luigi died suddenly. Shortly afterwards she was introduced to the yoga guru BKS Iyengar by the famous violin virtuoso Yehudi Menuhin. It was Yehudi Menuhin who “disovered” BKS Iyengar in 1951 and introduced him to the West. BKS Iyengar would go on to become world famous Yoga guru and Vanda had the good fortune to learn yoga from him. At this point practicing of yoga postures as done today was relatively unknown. She was almost 50, suffered from severe scoliosis, and was going through a difficult emotional period due to the death of her husband.

J. Krishnamurti would visit the Scaravelli Chalet in Gstaad, Switzerland and BKS Iyengar also visited at the same time to teach yoga to J. Krishnamurti. He also gave lessons to Vanda. Later she said in an interview, “I did not know it would help me, because I practiced it like tennis or any other game, for me it was fun. But it acted on me much more profoundly than I could understand at the time. A new life entered my body. In nature flowers bloom in spring and then again in autumn. This is what I felt was happening to me.”

A few years later she was introduced to Desikachar who opened the world of breathing to her. Desikachar was the son of the legendary T. Krishnamacharya who was also the guru of BKS Iyengar.

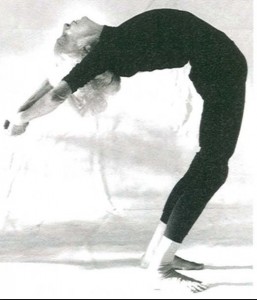

Vanda began practicing on her own and slowly discovered that the less she tried “to do” the postures and gave up wanting to be perfect, the more effortless and graceful her postures became. Just like she had arrived at Yoga by accident, so also she happened to come upon accidentally the idea of teaching yoga. Both she and J. Krishnamurti practiced yoga together when he visited Gstaad in summer. She noticed that he became exhausted from his yoga practice, and she taught him the techniques she had discovered so that he could do his practice effortlessly. In addition Vanda used Krishnamurti’s philosophy of “keep it simple” as a guideline throughout her practice. Krishnamurti used to say, “The mind needs to be clear and as empty as possible. Fill it with techniques and instructions and we’re back to the doing” This wisdom became the basis of her yoga teaching.

Vanda began teaching when she was 60. She had fewer than 10 students in all. She never charged money from her students. She taught because she felt compelled to do so. By now her children were adults and she was a free woman. She spent hours with her students and taught them one-on-one with an individualized practice. It was not easy to teach someone not to “do yoga” but to “discover it” on your own, to approach it fresh every time, and practice it as if doing meditation with an empty mind and with no expectations. Most of her direct students were already practicing yoga when they met her, but they saw what she was saying was deeply meaningful and they dedicated their lives to learn from her. Some of her students studied from her for 30 years.

Vanda Scaravelli’s philosophy was simple: “Yoga must not be practised to control the body: it is the opposite, it must bring freedom to the body, all the freedom it needs.” She encouraged her students to take their time – “there is no hurry, do not rush” – to do less, feel more. She taught the importance of listening deeply to what the body suggests before moving; to unwind, release unnecessary tension, and begin to simply be. “You must only undo. The more you undo, the more you are and the more things come to you. Don’t try to become; you are.”

Vanda deeply trusted yoga to sustain and heal the body. If she was sick or when she fell and shattered her hip, her constant question was ‘how soon can I do my exercises?’ because she knew that they would heal her. Once she was hit by a car and bounced off the hood. She went home and curled up like a little animal and did her breathing. Within a week, she was fine. Vanda refused anesthesia for root canals and once for the removal of a tooth; all the dentists in the office came to watch in amazement. Vanda saw these occasions as opportunities to “play” with breathing and pain.

It was never her intention to start a “Vanda Scaravelli” style of yoga. In fact she expressly prohibited her students from doing so. She once said, “Yoga cannot be organized, must not be organized.” She was following in the footsteps of her friend and Guru Krishnamurti who advocated a “pathless path” to truth. But just as Krishnamurti eventually did became a guru with a teaching and followers, Vanda Scaravelli also became a founder of a style of yoga that is known by her name.

She continued to practice yoga well into her late 80s. She died when she was 91. Her life shows that it is possible to take the best of the east and the best of the west and turn it into something original and beautiful.

Credit: This essay has borrowed liberally from various sites. Some of the links are provided in the “related” section. This has been written by Raj Shah and edited by Ketna Shah.

Related:

Essay on Vanda Scaravelli on Relax and Release website

Vanda Scaravelli: Her Legacy

When Movement becomes Meditation: The Legacy of Vanda Scaravelli

Lesson in Freedom

You may also like: The First Lady Of Yoga